I first became interested in Jocelyn

Brooke back in the early 1980's and I recently decided to rekindle and broaden

my knowledge of his work (and found there are no Kindle books of his!) I began

to look for some first editions and in doing this drifted around the web to see

what I could find. In doing so I came across a suggestion that a 'young friend'

of Brooke's was considering writing a biography of Peter Warlock (pseudonym of

Philip Heseltine) the English composer. This friend was suggested to be one Geoffrey

Poynton.

|

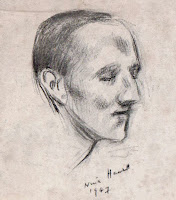

| Jocelyn Brooke by Nina Hamnett |

How did I first hear of Jocelyn Brooke?

Hard to remember now, but I think it was a review of the King Penguin edition

of the Orchid Trilogy published in1981. This trilogy consists

of three novels The Military Orchid, A Mine of Serpents and The

Goose Cathedral which are carefully described by Brooke as ‘not, strictly,

an autobiography’ and he concocted the neologism ‘Autobotanography’ as the best

description of The Military Orchid. This edition came with an

introduction by Anthony Powell and I was already a great fan of his, having

read the entire Dance twelve novel set. At the time I thought

it very amusing and felt it/they mirrored my life. My attachment was strong, so

the mere mention of an author whom Powell held in high regard was something I

just had to investigate. And, of course, as with everything else I've ever

become interested in, I started reading and there was no better way to begin

with Brooke than to buy this King Penguin.

Rereading the Introduction now, there

is the interesting suggestion of a 'Proust-Joyce-Firbank reading' lifestyle and

Brooke's interest in 'Decadence'. Just as this book was my introduction to

Brooke, was Powell's note my introduction to Firbank? Or, at least, his name? I

think it probably was. I was certainly well aware of Proust, Joyce and

Decadence, having arrived at this point via Oscar Wilde, several attempts to

read A la Recherché de Temps Perdue and an evening class

studying Ulysses (which culminated in a weekend in Dublin and a

fancy dress party where I went as the ‘s of Hely’s sandwich board men.) But Firbank was new and intriguing.

I read and loved the Orchid

Trilogy, The Military Orchid particularly: the hero's love of orchids

so closely matched to my own fascination with butterflies, also

originating in my childhood although I wouldn’t consider myself as precocious

as Brooke. I knew little of orchids (then, I do a little more now) other

than a few Wilde quotes:

I was thinking chiefly of flowers. Yesterday I cut

an orchid, for my button-hole. It was a marvellous spotted thing, as effective

as the seven deadly sins. In a thoughtless moment I asked one of the gardeners

what it was called. He told me it was a fine specimen of Robinsoniana, or

something dreadful of that kind. It is a sad truth, but we have lost the

faculty of giving lovely names to things. Names are everything.

As far as I know, Brooke never quoted this quip from The

Picture of Dorian Gray but he could have subverted it easily: yes the

orchids have Latin names but their English names are beautifully descriptive.

The recent purchase of Brooke's The Orchids of Britain, wonderful

illustrated by Gavin Bone, showed me this, as if The Military Orchid

hadn't: Green Man, Great Brown-Winged, Monkey, Bee, Lady’s Slipper,

Lizard….and, of course, the Military Orchid.

But the introduction of the

'Proust-Joyce-Firbank reading' lifestyle really arrives in descriptions of the

narrator's Oxford year and in The Goose Cathedral when the

hero and his mate Eric Anquetil (his only remaining friend from Oxford) lounge

on the immediately pre-war Sandgate beach reading their colourful Rainbow

editions of Firbank's works published by Duckworth. Their friendship is lazily

louche, involving most of a bottle of gin at their first meeting and summer

crawls of the many decrepit pubs of the Folkestone fishmarket: the principles

if not the geography of these activities I was very familiar with. The missing

ingredient, though, was Firbank with whom I was completely unfamiliar.

About half way through the volume, deep

in A Mine of Serpents, Brooke has the ‘legend’ Hew Dallas say:

...You haven't read Firbank? Oh my dear

you must - Beardsley in prose, but much better...

|

| Rainbow Edition of Cardinal Pirelli |

I remember reading an article about Firbank where this

literary/visual equivalence was repeated (however simplistic a view of Aubrey

Beardsley's oeuvre that seems to me now.) Beardsley I

definitely knew about. I'd bought the major (in all senses) book by Brian Reade

back in the 1970's and I had had posters of Siegfried with slayed dragon

and The Climax on my various bedroom's walls. This reference was clearly

to the later of Beardsley's works, those marvellously baroque illustrations for

Pope's Rape of the Lock and his work for The Savoy.Penguin

Modern Classics then published some Firbank: Valmouth, Prancing Nigger

and Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli, all in one

volume. Soon after reading these so-short 'novels' I bought a set of the

Rainbow editions myself, all previously owned by Desmond Flower, the editor of

Ernest Dowson's poems and letters. He had also worked on the Book-Collector's

Quarterly with A.J.A. Symons, the questor of Corvo and author of an

unfinished biography of Oscar Wilde.And - furthering my own quest - in a

bookshop some time later I found a light purple Rainbow edition with its faded

dust wrapper: it was Cardinal Pirelli and on the front free-endpaper was

the inscription:

To Geoffrey

Poynton

from

Jocelyn Brooke.

27 July 1946

|

| Brooke's dedication to Poynton |

So I had now performed some sort of

very slow and Einsteinly impossible backwards time-flip from the Geoffrey

Poynton I had only recently read about, back to the dedicatee of a book I had

owned for 30 years. Those being pre-broadband days, I was a subscriber to a

number of booksellers and was receiving catalogues from a dealer called Pagoda

Books. In the final catalogue was another Rainbow edition, possibly Vainglory,

which also contained the same inscription from Brooke. Before I could buy it,

Pagoda Books ceased to trade. I have never seen the book since but thought that

I might: and, indeed, I always think that I will. Here, then, was Brooke's

friend, although I was unaware of the evidence of his youth, the putative

biographer of Peter Warlock.

I cannot free myself from the thought

that Eric Anquetil of The Goose Cathedral 'might' 'be' the

fictional facade of Poynton. I suppose it is the existence - to my knowledge -

of two of the Firbank Rainbow editions dedicated to Poynton by Brooke which

leads me to that conclusion. The Goose Cathedral, to me, revels

in the reading of these books on Sandgate beach in the summer of 1939, mixed

with forebodings of war and meeting Pussy Wilkinson in Folkstone. This

character has his links to the mauve decade of the 1890's, having known Robbie

Ross, Reggie Turner “and had even, on one memorable occasion, been introduced

(at Dieppe) to none other than 'Sebastian Melmoth’ himself.” (Melmoth is Wilde,

released after two years hard labour in prison.)

With Author’s Notes to the first two

novels of the trilogy and a Preface to The Goose Cathedral Brooke

goes out of his way to explain the tenuous nature of the links between his

books and real life (his life):

…the author has taken a novelist’s liberties both

with persons and institutions.

Maybe he doth

protest too much? In his Preface he continues with this

explanation but mentions that (as Proust allows his readers to assume)

the narrator’s:

...Christian name happens to be

the same as the author's.

He fails to mention in the preface that in the actual

novel the narrator’s surname also ‘happens to be the same as the author's.'

Could the link between an author called ‘Jocelyn Brooke’ and a supposedly

fictional narrator called ‘Jocelyn Brooke’ be an indicator that other

characters also are simulacra of real people?

In 1951 Brooke published a

study of Ronald Firbank which contains statements relevant to this piece. About Firbank and his interests, literary and other:

His taste for the nineties

persisted (this was approximately 1909/11); he was collecting rare editions of

Wilde, Beardsley, Dowson and the rest. It is said, too, that about this time he

became deeply interested in magic, under the influence of Aleister Crowley…

In The Goose Cathedral, Anquetil, and Brooke,

search for forgotten eighteenth century poets to write about and Anquetil finds

one in William Penycuick a 'dix-huitieme' who he writes a book about and

continues to research, chasing him to Sicily. There here seemingly behaved like

an early Aleister Crowley. Which brings me back to Philip Warlock:

His name is surrounded by rumours of involvement with the occult, an

interest which he shared with others in the Bohemian world of the early 20th

century -- for example the novelist Mary Butts asserted that it was Warlock who

initially introduced her to these subjects. Aleister Crowley, in his book Magick

Without Tears, affirms that Warlock's death was the result of an Abramelin

magical operation aimed at winning his wife back. Other less conventional

aspects of Peter Warlock's life include experimentation with cannabis tincture,

a gift for the composition of obscene limericks and a marked interest in

flagellation.

In Brooke’s Ronald Firbank he comments upon Firbank’s

writing:

There is, in fact, a curious

ambivalence in his work, a perpetual conflict between his ninetyish sensibility

and a cynical self-mockery which somewhat recalls the similar case of his

contemporary, Philip Heseltine. In Heseltine the two modes exist separately:

“Peter Warlock” bears little or no relation to the composer of The Curlew.

Philip Warlock's music, or personality, or both, was so important

to Brooke that, uniquely, he used an excerpt from one of his works as an

epigraph to The Scapegoat.

To

try and understand this and help to see if I could unravel the Peter Warlock

and Geoffrey Poynton enigmas would need me to undertake a little more research.

to be continued...

No comments:

Post a Comment